I come from a family of tall, attractive athletes. I have three siblings, and all of them are over six feet. (My sister Carey, the shortest of the three, is 6’1”.) All the other Saulter siblings played sports at a high level. And all of them have head-turning looks.

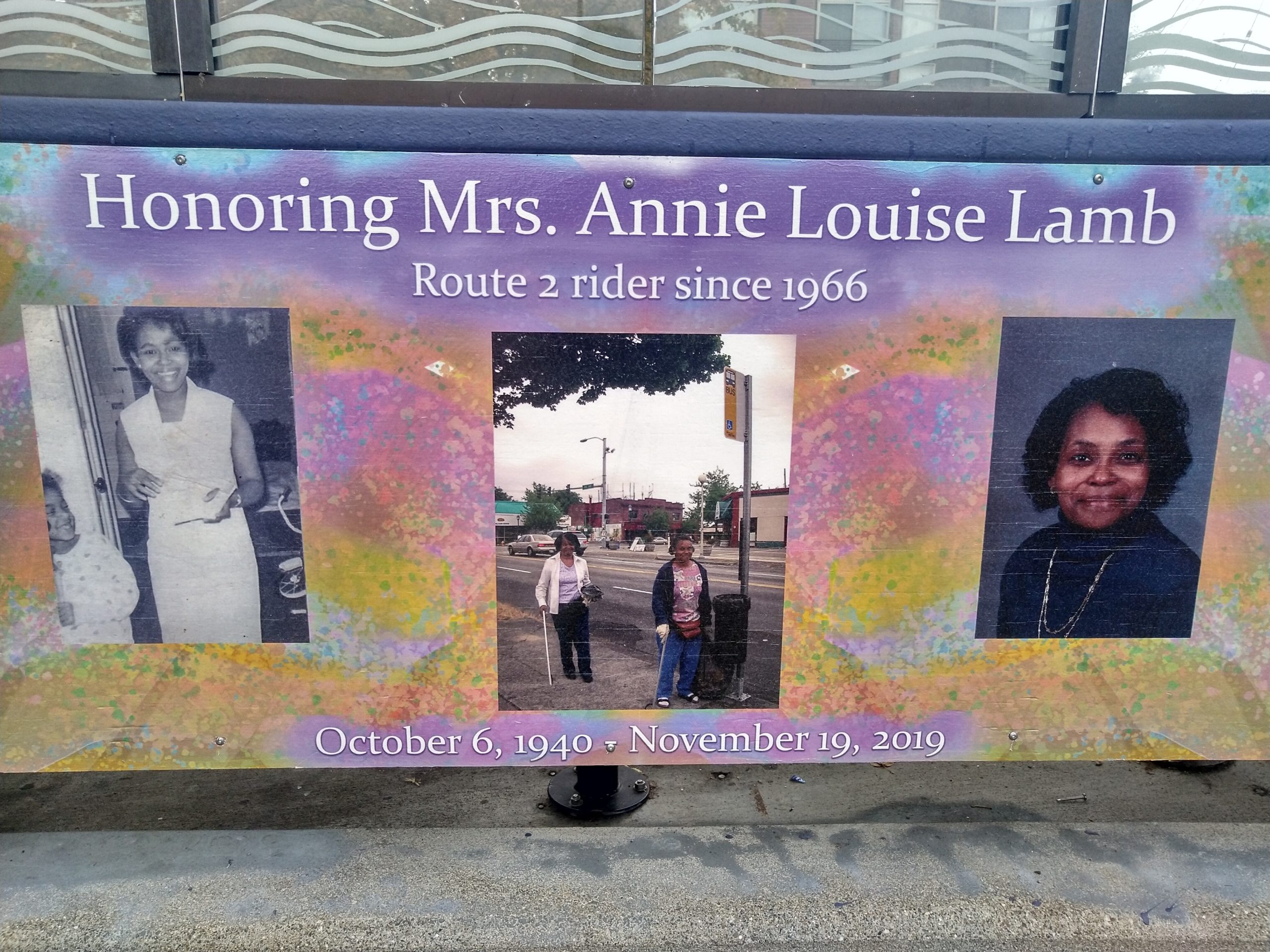

Unfortunately, those genes missed me. I am barely 5’5”. I suck at pretty much every sport (and TBH, don’t particularly enjoy playing). And the looks … well, let’s just say that no one will ever mistake me for a model. Then again, I did spend a year as a model bus rider back in the day.

I digress.

The only trait I share with my sporty-looker siblings is that I love watching sports. Basketball is by far my favorite, and the team I loved my whole life—starting before I could have imagined the existence of a WNBA—was the Sonics (RIP). I am tempted to spend several paragraphs ranting about the evils of the NBA and professional sports in general, but I will refrain for now and try to stay focused(ish).

This year, for my birthday, my brother Jeremy gave me a gorgeous classic Sonics jacket. It’s far too cool for someone like me, but you don’t have to ask me twice to represent my city. The jacket is lightweight, so I wore it a lot in late spring, before the burning fires of hell descended.

I was wearing the jacket when I boarded the 3 early last month, on my way to get a tattoo. (More on that in a future post.) The driver—who, happened to be tall, attractive,* and athletic—was wearing a Sonics mask. We shared the raised eyebrow of recognition and then exchanged compliments.

“Nice mask.”

“I like your jacket.”

It was midday and somewhat early in the route, so for a few stops, I was the only passenger on the bus. I paused at the front to answer a few of his questions—where I had gotten the jacket, who was my all-time favorite player—thinking we would exchange a few pleasantries before I made my way to a seat near the back door. But he was so friendly and curious and interesting that we kept talking, and I eventually settled into the BDP seat for a real conversation—at least, as real of a conversation as you can have from several feet away, through masks and a plexiglass barrier.

We started with the Sonics, then moved quickly to my current love, the Storm, who were (are) having a great season. By the time he asked me which sports I played, there were several other passengers on the bus to hear my loud (though muffled) cackle.

I asked him how long he had been driving for Metro and whether he liked it. Four years** and yes. Mostly, anyway. We talked about our kids. He has an eight-year old who is kind and loves football and video games and wants to be just like his dad. Finally, as we headed down the hill from Harborview, I asked his name. Robert.***

At Third and James, a wheelchair passenger was waiting to board. I recognized this man from well over a decade of seeing him on buses and at stops. Robert recognized him, too. They greeted each other like old friends while Robert lowered the ramp, and I moved back to make room for the chair.

For the rest of the ride, I had a front row seat to their conversation. I listened as this elderly man, whose life beyond the bus I had never considered, talked of his younger days, of decisions he wished he had (or hadn’t) made, of relationships that had ended badly. I had never, before that day, seen this man smile or laugh. I watched in amazement as he called Robert by his name, gave him advice, and told him that his “friendly personality” made a difference.

“You’re a really good guy, man,” he said, just as I stood to exit.

Robert paused to look in his rear-view mirror before responding to the compliment.

“Bye, Carla,” he said. “It was really nice talking to you.”

________

* He even favored my brother a bit.

** To be honest, I don’t remember what he said, but I’m pretty sure it was less than five.

***It’s not his real name, but I’m not trying to share all the man’s business on the internet.