Late last month, at around 4-ish on a Wednesday afternoon, Chicklet and I found ourselves on a 27 heading home from downtown. Seats were scarce when we boarded, but we found two together in the back row—a safe distance from other passengers—and spent the ride discussing my longtime riding partner‘s expectations and hopes for her final year of middle school (!!!).

When we arrived at 23rd and Yesler, per usual, the bus cleared out, leaving only Chicklet and me, who planned to exit at the next stop, and a young white woman, who was engrossed in her laptop at the other end of the back row.

After the mass exodus, a sixty-ish Black woman boarded, carrying a shopping bag in each hand. She was wearing a teal, v-neck halter top; fitted floral pants; and a black, bobbed wig. As she stepped aboard, she nodded to the driver and, in a melodious voice tinged with an accent I couldn’t place, and said matter-of-factly, “I don’t have a card.”

She looked fabulous—attractive, stylish, and somehow simultaneously seasoned and youthful—so I watched her walk all the way to her seat.

It wasn’t until she was settled—in a window seat on the right side of the bus, about midway down the aisle—that I noticed she wasn’t wearing a mask. The driver, a stocky white man in his mid to late thirties, apparently noticed too. His voice, muffled by his own mask, drifted toward the back of the bus.

“Excuse me. Excuse me, ma’am?”

The woman did not reply or indicate that she had heard him.

With the bus still parked at the stop, the driver shifted in his seat and turned his body in the direction of the woman. He got louder—“EXCUSE ME???”—then started rapping his knuckles on the plexiglass (Covid) safety barrier that separated his seat from the rest of the bus.

Still, there was no response.

Assuming that the woman wasn’t aware that the driver was talking to her, and anxious to get moving, I hustled down the aisle to her seat. She had her phone to her ear but was staring straight ahead and not actually talking. I leaned toward her and said, “I think he’s trying to get your attention.”

She did not turn her head or even move her eyes in my direction. I repeated myself and waited for a few more seconds, then eventually returned to Chicklet, who was widening her eyes and cocking her head in the universal gesture for “WTF?”

The driver continued to call to the woman, banging on the plexiglass barrier, then eventually standing up. She continued to sit serenely, almost frozen in place, with her phone to her ear.

Finally, the driver slipped past the barrier, grabbed a mask from the dispenser, and waved it in front of her.

“Hellloooooo?” he said, his tone reflecting his now high level of exasperation. “Can you put one of these on?

She said, “No.”

The driver paused for a beat, then blurted out something about masks being required on the bus.

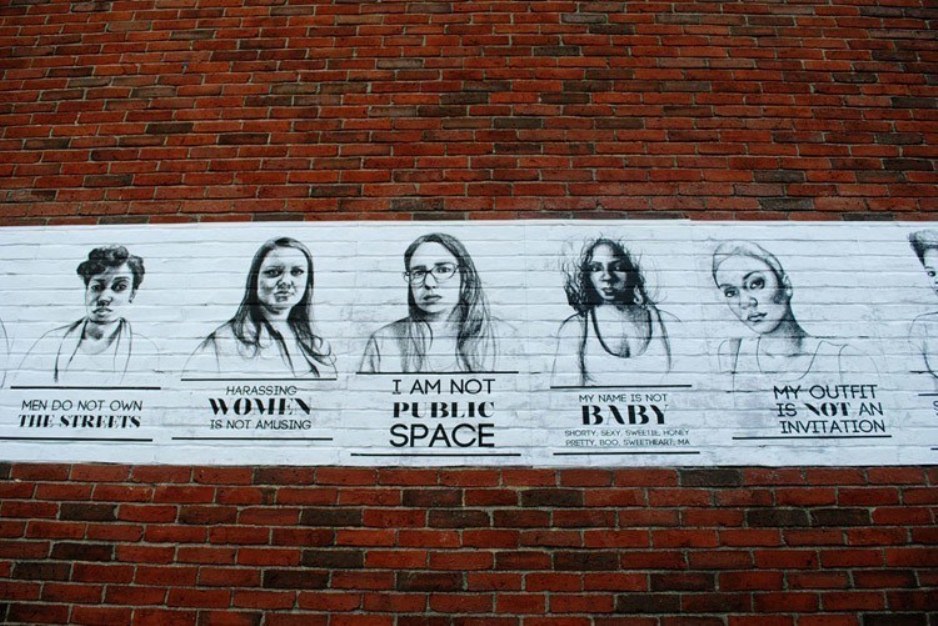

The woman said, “You’re being violent with me.”

The driver tried to justify his behavior, saying he’d raised his voice because he wasn’t sure she’d heard him.

The woman remained silent.

“Well, we’re not going anywhere until you put this on,” he said, dropping the mask on the seat in front of her.

She said, “That’s fine.”

The driver returned to his seat. After a moment, he turned off the bus and opened the doors, then stepped outside to make a call. He explained to the person on the other end—his shift coordinator? the transit police?—that he had a passenger who was refusing to wear a mask and that he wasn’t going to leave the stop until she did.

While he was talking, the woman pulled out a book.

After the driver finished his call, he returned to the woman’s seat and told her that someone was coming to escort her off the bus if she didn’t put on a mask.

“It’s your choice,” he said.

She said, for the second time, “That’s fine,” and continued to calmly read her book.

I could feel the tension rising in my body as I anticipated the inevitable confrontation. We could have easily walked home from the stop where the bus was parked, but I knew I had to stay put, if only as a witness to whatever happened next.

The woman’s extreme calm intrigued me. Was she as unbothered as she seemed? Was she terrified but determined to stand her ground? And why wouldn’t she put on a mask?

Part of me was pissed at her. From my perception of the interaction, she was being ridiculous and unreasonable, not to mention selfish. As the mama of an unvaccinated 11-year old who has been hospitalized twice with asthma exacerbations, I don’t have patience for people who believe that their personal preferences are more important that the lives and health of the people they share the world with.

But part of me felt protective. I thought of the many reasons (historical and otherwise) she was justified to insist on being treated with dignity. And I knew for sure that I didn’t want to see her manhandled or forcibly removed from the bus.

As we waited, the three of us in the back row whispered to each other, wondering what would happen, sympathizing with bus drivers and everyone else tasked with enforcing mask mandates.

Within a couple of minutes, the driver returned to the woman’s seat.

“Can I ask you something? Why won’t you wear a mask?” His tone was curious, even conciliatory.

Hers was as firm and resolved as ever. “I’m not going to discuss it with you.”

I often say that drivers need extra emotional and spiritual support to do their jobs well. Of course this is true. But they also need emotional and spiritual support to cope with the impossible situations that prevent them from doing their jobs well. Because really, what was this driver supposed to do?

What he did was turn to the three of us in the back, arms raised in helplessness and frustration.

“Sorry, guys,” he said.

Then he stepped outside again to wait.

Chicklet announced that she had to go to the bathroom. I asked if she could hold it (hilarious, coming from someone whose life revolves around restroom access). She rolled her eyes.

“Mom, how long are we going to sit here?”

As it turned out, not long. Moments after her question, the driver abruptly returned to his seat, sighed loudly, started up the bus, sighed again, and pulled away from the stop. Chicklet pulled the bell, and four blocks later, we stepped away from the whatever the hell had just happened.

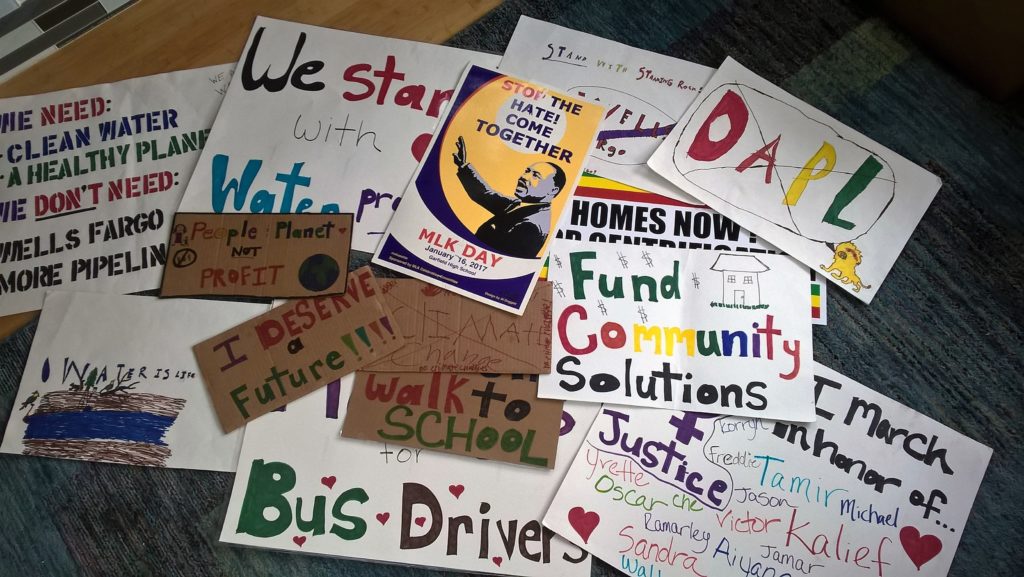

As we walked the rest of the way home, I wondered—for perhaps the millionth time—how we can share space with other humans in a way that holds people accountable and honors their dignity? How can we be together in a way that keeps everyone safe? I used to think that, in order to justify my love of the bus, in order to justify my ramblings on this blog, I needed to have an answer to that question. The truth is, after all these years of riding, I have no effing idea.

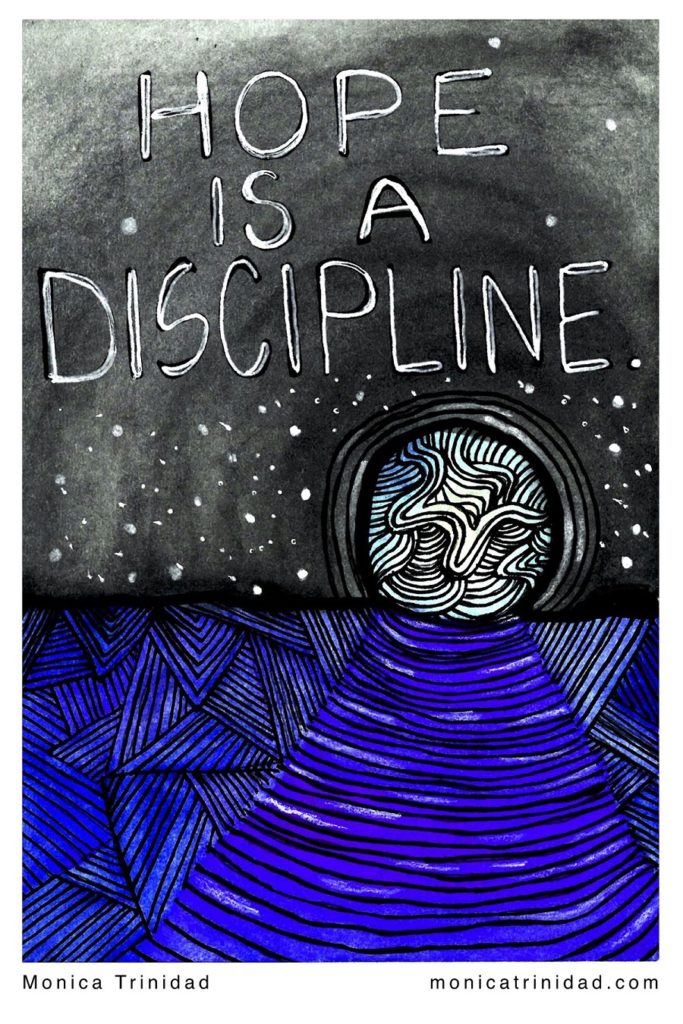

All I have is hope. Not the kind that overlooks challenges, but the kind born of discipline and a determination to continue to practice being in community, even—especially—when the urge to turn away is strong. Because if we don’t keep trying, our only purpose is to survive our time here. I want more.

And so I lift up that bus driver, that he might know the inherent dignity and beauty in his work. May he understand that he did the best he could under the circumstances, and that sometimes there is no good response to an impossible situation. May this experience deepen his compassion and empathy—for himself, and for his most challenging passengers. May he find the vision and grace to imagine a different response to the impossible situations he encounters in the future.

I lift up that determined woman. May she continue to prioritize her dignity, which she maintained throughout a very tense, public interaction. May this experience encourage her to consider the dignity and well-being of others in her future actions. May she come to understand that her preferences don’t supersede others’ right to live. May she heal from those times when people have treated her in a less-than-dignified manner, and may she be treated with dignity in all her future encounters.

Ase.