OBC, n: Original bus chick. A person who has actively chosen transit over other forms of transportation for several decades; an extremely experienced transit rider.

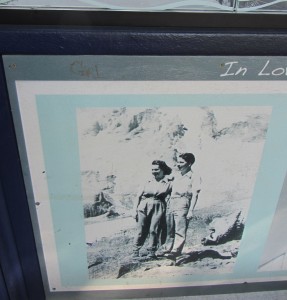

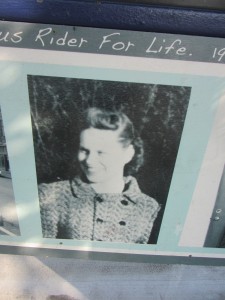

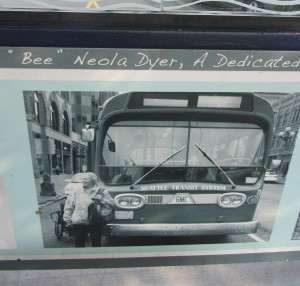

A couple of years ago, King County Metro installed a bus shelter memorializing Beulah Dyer, a lifelong Seattle transit rider who passed away in 2011, at the age of 90. Born in Ballard in 1921, Mrs. Dyer started riding transit at a very young age. She never stopped.

She never tried to get a driver’s license, believing the bus was “always better.”

Dyer took up to six bus trips a day – to shop, visit with friends, attend classes, and volunteer – and was known as a “walking bus schedule.” Friends report that she could tell you, without having to look it up, which bus to take to any destination between Des Moines and Everett, and when you needed to be at the bus stop.

She raised her daughter, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren to be bus riders. Every story she told seemed to begin with what bus she caught and how long it took her to get there, and ended with the buses she rode to get home.

Talk about an OBC! Young (and middle-aged) bus chicks, bow down.

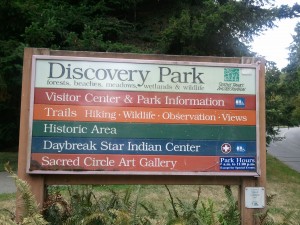

On Tuesday, I finally had a chance to see Beulah Dyer’s bus shelter in person.

After visiting Mrs. Dyer’s stomping grounds and seeing the photos on the shelter, I wanted to know more about her: what her hobbies were, the hardships and triumphs she experienced, her favorite color and food. I searched the Internet but was only able to find this 2001 news story about her 80th birthday celebration, which was held on the 65.

Metro Transit and Dyer’s family threw a surprise 80th birthday party on the Route 65 bus. The guests included King County Executive Ron Sims and Metro General Manager Rick Walsh.

She guessed something was happening when her son, sister, brother, sister-in-law and two adult granddaughters showed up at her bus stop when she was leaving University Village.

“I don’t know what you’re up to but it had better not be a stripper,” she said.

Ten blocks before her stop, Sims led a parade of celebrants onto the articulated bus. Her favorite driver, Gregory Nash, carried the cake.

Metro leaders learned about Dyer’s loyalty when her granddaughter, Jahna Dyer, wrote a letter to thank them for taking such good care of her grandmother.

Sims and Walsh presented Dyer with flowers, a certificate, Metro commuter mug, umbrella and an insulated lunch bag. Metro’s uniform supplier threw in a green Metro cardigan sweater.

If I ride the bus for 40 more years, can I get a Metro cardigan? Seriously. I have been trying to figure out how to get my hands on one of those for at least a decade. And just to put it out there in the universe, I won’t be mad if there’s a stripper involved. Kidding! (Sort of.)

But I digress.

My grandma moved to Seattle in the early 1930s. Though her experiences—as a black woman living in the Central Area–were certainly significantly different than Mrs. Dyer’s, the two women shared in common a love of buses. My father, who was born in 1939, spent his childhood riding streetcars and trolley buses in this town and has many stories of the velvety seats, the sounds the vehicles made, and how the drivers would help his mother on and off when he and his siblings were small.

When I was growing up, I remember wondering why my grandma always insisted on walking and busing to get around, even when others were willing—would, in fact, have preferred—to give her a ride. Now, I am in her shoes: trying to explain that yes, I really do want to take the bus, and no, it’s not (usually) a hardship or an inconvenience; it is part of who I am.

If I am given the gift of long life, I hope it will remain so.