Several of the writers I most admire say that they write to make sense of the world, to explore topics that trouble them or make them curious. Through their wisdom, I have begun to understand that writing isn’t about having answers; it’s about looking for them. Hallelujah (!), because 1) I have no answers – ever, and 2) asking questions is my specialty. (Guess I forgot one skill back when I was making a list.) Folks, if you could get paid for wondering stuff, I’d have a lucrative career on my hands.

I digress.

One topic I spend a lot of time considering is community. Resilient, interdependent, connected communities are critically important to our mental and physical well being. They are necessary for educating children, caring for elders, protecting our natural environment, and building movements. And yet, very few people I know can claim themselves a part of one.

On a superficial level, I am steeped in community. I am married to a man I adore and am mama to two amazing children. I live in the city where I was born and raised (a physical place I love deeply), and I still have family – including two nieces and a nephew (!!!) – and longtime friends here. I like and spend time with my neighbors. My kids attend the local public school, which is a half mile from our home, and both my spouse and I are actively involved there. Our church is a mile away. We vote and volunteer. And, because we are bus riders, we regularly share space with the people we share the world with.

All of this sounds good on paper, but in reality, it’s a disjointed mess. My in-laws live thousands of miles away. My mother is deceased. My father is out of town for several months every year. My two siblings who still live in the area are long freeway rides away. All of my closest girlfriends live either across town or across the country and are so busy with work and family that even phone conversations are a rarity. And while our church is close to home, only a handful of our fellow members still live in the neighborhood. Even our pastor lives in Kent.

What this means is that the people I have deep, long-term, soulful connections with are not the people I see every day. I am fortunate that my neighbors, the people I do see every day, are fantastic. We are slowly building bonds, but they are not (yet) the people who know my secrets or who I would call on to hold my family up through a crisis. I am making an effort to spend more time with them, but making time to see people is not the same as making a life with people. And to be honest, I’m not even sure how to do that.

The details of my specific situation aren’t particularly important, except for the fact that they aren’t particularly unique. Many of my friends and acquaintances are in the same boat: living their daily lives far from those they hold dearest, and lacking the time or ability to connect in meaningful ways with people in their immediate vicinity.

So how did we get here? What has brought us to this place of such profound disconnection? What does community even look like, and why are so many of us missing it?

We experience community in many different ways, including, these days, through the world-shrinking miracle of the internet. But what strikes me as most critical — and also most lacking — is a robust, connected, compassionate network in one’s immediate physical location. Instead of merely access points to the other places we go every day, our neighborhoods should be unique, diverse, dynamic, home bases, where we care for one another and the physical space we occupy, and truly build our lives.

OK, yeah. It sounds a little “woo woo” – and a lot naïve. I realize, perhaps better than anyone, that the idea of community is often a lot rosier than the reality. Dealing with people is hard. Dealing with conflicting ideas and interests is hard. But we have buried our humanity so deeply under the layers of nonsense our culture prioritizes, we have made it a lot harder than it needs to be.

In the United States, we have a history that disconnects us, on many levels. I’m not going to spend a lot of time on a history lesson, but I will point out that building a nation through settler colonialism, genocide, slavery, oppression, and exploitation of the natural environment tends have a negative impact on community.

The people who colonized this part of the world – perhaps because they didn’t originate in or understand the places they settled – lacked reverence for them. Again and again, settlers arrived in a place, assessed its “value” by the natural resources that could be dug up, cut down, caught, or killed. Human beings were also devalued – exploited, oppressed, or exterminated – in service of the goal of material wealth. “Race” became the justification for this devaluation – and it continues to inform our connection to place and to each other.

The system of separation, of using race to create winners and losers, of privileged people seeking the next “frontier” to exploit for profit, persists. In our extractive, profit-focused economy, places are interchangeable. Companies move on when resources are exhausted, or when another location promises cheaper labor, lower taxes, or fewer regulations. The wealthy grow wealthier by actively undermining community, while the victims of this exploitative way of life are either displaced, forced to leave their homes in search of work, or incarcerated.

Even if we are fortunate enough to find a means of survival and a permanent place to settle, the structure of our society prevents us from being in community. Most of us have to work long and hard – sometimes at more than one job – just to get by. (Don’t get me started on the cost of living in this town.) Those of us who are privileged enough to earn decent wages often work at jobs that require long hours and round-the-clock availability. All that time spent working leaves us precious little time for people.

Our built environment also fosters isolation. For many decades, communities have been built to prioritize cars — with multiple lanes, no sidewalks, and few public gathering spaces. Travel happens in an isolated bubble between parking structures and involves no contact with human beings. Neighborhoods become less important, because we can drive anywhere we want to go. Coveted homes in these car-centric communities are built to be self-contained. Their big yards, rec rooms, and entertainment centers preclude any need to interact with others for leisure.

All of this (plus the complete absence of a social safety net and sane family leave policies) creates a society in which we are disconnected from the fact of our interdependence. We see the world in terms of ourselves, our partners and children — and possibly our extended families. But even most families have a sense of impermanence. Our kids grow up, move away – often, far away – in search of opportunity or independence and start their own families. There is no shared memory, no inter-generational support system, no continuity of connection.

No wonder we feel so alone.

I don’t know how to build the beautiful communities I envision. (Shoot, I don’t even know how to keep my own children from arguing.) But what I do know is that we cannot build anything until we start digging ourselves out from under all the layers of racism, individualism, and materialism and rediscover our humanity.

We must be willing to acknowledge, understand, and atone for our nation’s history. This means that the truth must be told, from a variety of perspectives, in formal and informal settings, at every opportunity.

We must radically restructure our economic priorities. We might not be able to overhaul our entire economic system, but we can act in small and large ways to prioritize human lives and relationships over productivity and profit. Obviously, we can vote and advocate for appropriate policies. But we can also lean on each other when we face economic pressure by sharing our skills and resources. We can offer – and ask for – help when it is needed.

We must foster a sense of place. In the United States in 2016, it is rare for people to settle in the same physical location for multiple generations. Mobility is part of who we are. But, we can work to build resilient communities while we live in them. We can do this by learning the natural and human history of the places we live and trying to understand how that history informs what is happening in the present. We can do this by meeting our neighbors – and finding ways to interact with them beyond the obligatory greeting at the mailbox. We can do this by giving of ourselves — planting trees, picking up trash, coaching a team — and taking advantage of local resources. And we can do this by getting outside as often as possible. Walking anywhere, even if it is just around the block, provides an opportunity to see our neighborhoods from a different perspective and to rejuvenate our spirits with a little fresh air and exercise.

So much is wrong with the way we live today. Our problems are structural, but they are also spiritual. They are destroying our natural environment, but they are also threatening our emotional well being by keeping us self-centered, lonely, and sedentary. The only way to respond is by making choices that directly counteract the forces that separate us.

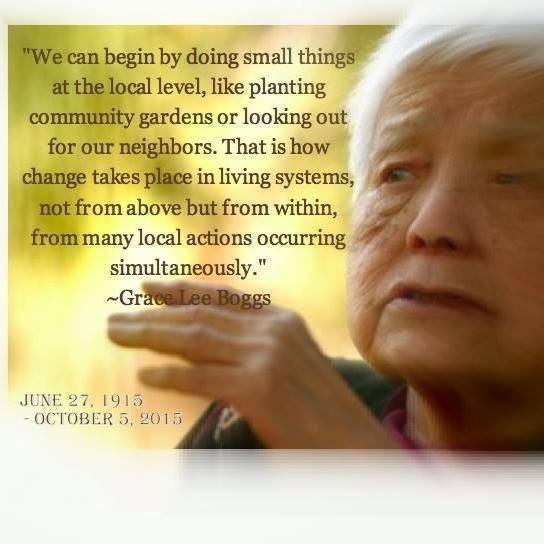

I am encouraged by the perspective of one of my sheroes, Grace Lee Boggs, who taught us that change isn’t a top-down process. Instead, she said, it happens “from many small actions occurring simultaneously.” Here’s to using our lives — and our daily, small, actions — to improve the systems we’re a part of.