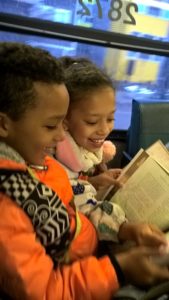

I realize that this is a bit of a cliché, but I’m going to say it because it’s the truth: My greatest spiritual teachers are my children. I don’t know if I believe all the woo-woo talk about our children choosing us or whatever, but I know for sure that mine have brought me the exact lessons I needed to learn. HBE taught me, first and most importantly, that love is a verb. He also taught me how to be flexible. Busling teaches me what freedom looks like. And Chicklet, my firstborn, teaches me how take care of myself.

I have never been good at boundaries. I struggle to understand where I end and other people begin. If someone near me is in pain, I can’t feel comfortable. If a friend tells me they have a problem, I immediately feel responsible for it. I worry and fret and strategize as if the problem were my own. I will give money to anyone who asks, for pretty much any reason and regardless of that person’s financial track record, because the idea of not sharing seems selfish to me.

When loved ones tell me that this might not be the healthiest approach to life, I nod and agree. I say things like, “Yes, I need to get better at saying no.” But secretly, I think my approach is right. After all, the problem in our so-called society is not too much concern about others; it’s too little concern about others. In American culture, there is so much emphasis on what we deserve—on “property rights” and self-care and finding your bliss and standing your ground—and so little emphasis on what we owe. This excessive focus on self has wrought the misery, violence, disharmony, and sickness that surrounds us.

Where do I end? It’s hard to say. Because we all live on the same planet. Because suffering is not contained. Because we are an interdependent species that relies on interdependent ecosystems to survive.

The problem is, my lack of boundaries feels less like interdependence and more like giving myself away. It makes me anxious and exhausted and resentful. Can an anxious, exhausted, resentful person build a beautiful, whole family, community, or world?

What I’m beginning to learn is that the world needs balance. I can’t create harmony by giving myself away any more than my neighbor can by taking more than she needs. Some of us must learn to say yes more, and some of us must learn to say no more. Right now, on my personal spiritual journey, I need to learn to say no more.

Enter my 14-year-old daughter, namesake of the woman who uttered one of the loudest NOs in the history of this nation.

Chicklet was born with boundaries. She wasn’t one of those “good” babies everybody cooed over. She wasn’t friendly to strangers. She wouldn’t let just anyone—or actually, anyone other than her parents—hold her. If I left her with a caregiver or family member, she would cry—loudly and indignantly—until I returned.

For years, Chicklet hated school, for a lot of valid reasons. (Tbh, she still low-key hates it.) When adults at church or in our social circles would ask her how school was going, instead of following the standard, polite script and saying, “great!” (or at the very least, “fine”), she would tell the truth: bullying was rampant, the curriculum was dull and repetitive, recess was too short and too limited, the cafeteria was too loud, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera.

I used to think that Chicklet’s refusal to play nice was something that needed to be corrected. Why wasn’t she friendlier? More pleasant? More agreeable? Why wasn’t she easy?

Over these 14 years, I have come to understand my kid’s lack of pretense as a gift. For one thing, she is a lot better than I am at being honest. It’s not that I lie. At least, I don’t deliberately deceive people. But I am not exactly truthful, either.

My personality has been built around making other people comfortable. This shows up in every area of my life, including—maybe even especially—my life on the bus. I wonder how many times I have smiled at a man who has disrespected me on the street or engaged in conversation with someone who made me uncomfortable. I wonder how many times I’ve dutifully answered intrusive questions about my ethnicity, just to put an end to the awkwardness of the interrogation. I wonder how many times I’ve said “not at all” when someone asks if I mind if they open the window, even though I very much do mind. I believe in the beauty of sharing space with other people, but I haven’t learned to do it authentically, without diminishing myself.

This is what my daughter has to teach me. Chicklet understands that we don’t build the beloved community by being “pleasant.” We do it by being honest about our needs. She shows me this again and again.

Once, a few years ago, we were visiting my friend Kelley and her kids, and Kelley offered us something to drink.

I have known Kelley since we were six years old. My kids call her auntie. She is family. And yet, without even considering whether either I or my child might be thirsty, I responded, reflexively, “Oh no, we’re fine.”

When Kelley left the room to put away our coats, Chicklet looked at me reproachfully and asked, “Mom, why do you always say I don’t want something without even asking me?”

Another time, when Chicklet was just six years old, a young man approached our family as we were walking home from the 27 stop. The man was clearly intoxicated but not—at least in my adult estimation—threatening. After saying hello to all of us, he put his fist out, at Chicklet’s level, and asked for a pound. I waited for her to play along, to give this man what he was asking for so that we could all smile and laugh (Kids, amirite?), and then the four of us could continue on our way.

Chicklet looked at the man’s hand but did not move. She knew, even at her young age, what was expected of her. Be polite to adults. Don’t be disrespectful. And for God’s sake, don’t be inconvenient. But she also knew that she didn’t want to comply with a stranger’s demand for physical contact. So, she she maneuvered that narrow space of agency as well as she could.

With her eye still on the man’s fist, she said, matter-of-factly, “My knuckles are hurting.”

The man shrugged off the slight and tried again, this time with an open hand.

“How about a high five then?”

By this time, I was feeling the awkwardness. The man was embarrassing himself and by extension, me. My lofty—and loudly proclaimed—beliefs about bodily autonomy and girls claiming their power evaporated in that moment, and all I could think was, Can she just give him a freaking high five already so this can be over with?

My child looked from the man’s hand to her own and then directly into his eyes.

Then she said, “I think my hand is hurting, too.”

That moment will be seared in my memory for all eternity. It was the moment my daughter showed me a mirror, and it reflected my cowardice and dishonesty.

Chicklet doesn’t give herself away to make other people comfortable, not even when her own mother subtly (and not-so-subtly) encourages her to. She is responsible to herself and her truth. She is not responsible for your feelings.

This is how we keep our spirits intact when we share space with other humans—on buses, in the street, and everywhere else. We be kind. And we hold the fucking line.