Even before COVID-19, I didn’t fly much. Like my decision not to drive, it started as an attempt to limit the resources I—only one human out of billions—consume. But it soon became a way of life that suited me: staying grounded, finding adventure and newness and discovery close to home. We take the family to Detroit once a year to visit my in-laws, and occasionally, my spouse travels for work. But mostly, we stay put or find alternatives to flying.

The biggest thing I miss about traveling is, interestingly, the same thing I miss about driving: visiting people I love. So many girlfriends I live far from have asked and asked (and asked) to schedule a girls’ trip, and I always find a reason to put it off.

But in late January, my friend of many years, C, lost her mother, and staying put was not an option. C requested that, in lieu of traveling to New Jersey for the funeral, our friend T and I visit her in the DMV after it was over, during the quiet, lonely time after the chaos.

T and I made the trip in the last days of February. It was a perfect visit, spent mostly catching up: hours of sharing, laughing, crying, eating, drinking, and (bonus!) riding the Metro.

Because I had never been, we visited THE museum, and it was every bit as profound and beautiful as I had imagined. I felt all the feelings. We stayed all day.

Image description: Exterior of the National Museum of African American History and Culture

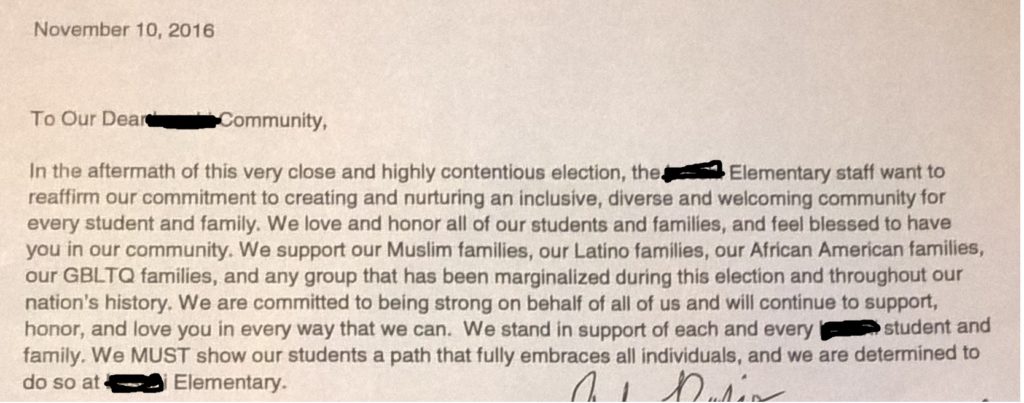

Right before the museum closed, I happened upon a small book in the gift shop: Rosa Parks in Her Own Words. If you are a longtime reader of this blog, you know that Rosa Louise McCauley Parks is one of my sheroes—certainly because of her involvement in the Montgomery Bus Boycott, which is one of the most remarkable stories of organizing and solidarity and commitment and resilience in the history of humanity. But also because of the incomparable courage and dedication to justice that she demonstrated throughout her lifetime of activism.

Rosa Parks is my chosen ancestor. My firstborn carries her name. She is a guiding light.

So of course I bought the book, which was published early this year and includes letters and personal notes and other papers that were only recently made publicly available.

In the evenings, after C, T, and I had talked ourselves out, I would lie on my hotel bed and flip through the pages, staring at the photographs of her handwritten notes, feeling equal parts voyeur (Should her private papers really be available to strangers?) and loyal daughter learning sacred traditions.

Image description: Book cover of Rosa Parks in Her Own Words

In the middle of our trip, T received a text from a friend back home. There’d been a death from COVID-19 near Seattle.

Before that text, coronavirus was in our consciousness but not top of mind. We’d heard about the fast spread in China and about the first known U.S. case being identified in our state. Weeks before we left on our trip, elected officials and public health experts had begun encouraging us to wash our hands thoroughly and frequently. News of the death was alarming, but coronavirus didn’t feel like a direct threat.

I made it home on the evening of March 1, full from my girl time, ready to rejoin my family and return to my routines: library trips, neighbor visits, walks to dance class, and of course, bus rides.

Instead, I returned to an escalating emergency.

Performances canceled.

Fundraisers canceled.

A memorial service (for someone very special to me) canceled.

When school was canceled, I knew we had crossed into unknown territory.

On the first morning of everyone home, I woke up early. I felt a need to serve my family, to do something grounding and comforting that would bring us together at the beginning of a scary and uncertain time.

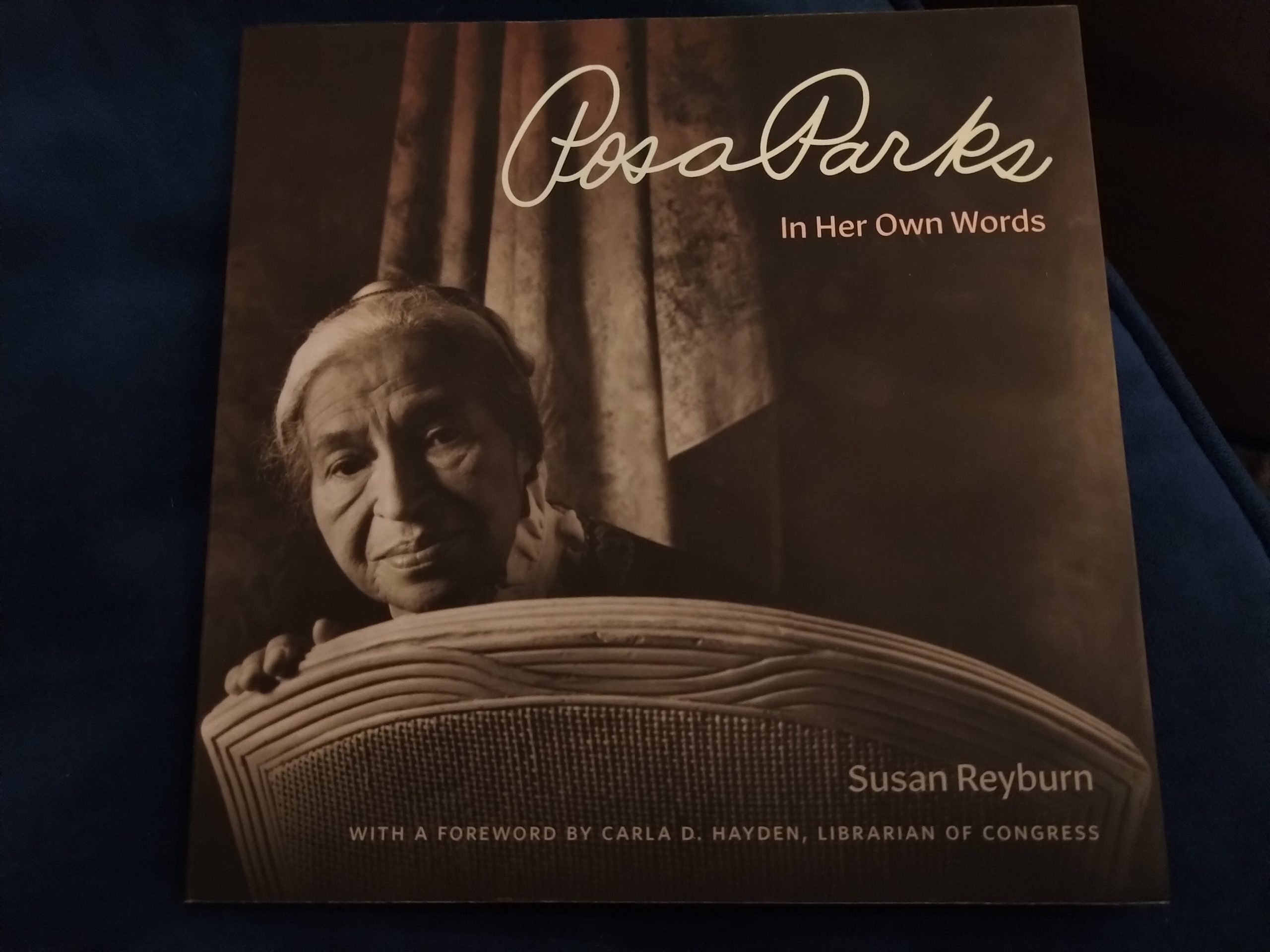

I opened that little book I had bought in DC a few weeks (and an entire lifetime) earlier and turned to the page with the photograph of Ancestor Rosa’s famous (in her family) “featherlite” pancake recipe, written in her own lovely handwriting on the back of an envelope.

Image description: A photo of Rosa Parks’ recipe for “featherlite pancakes”

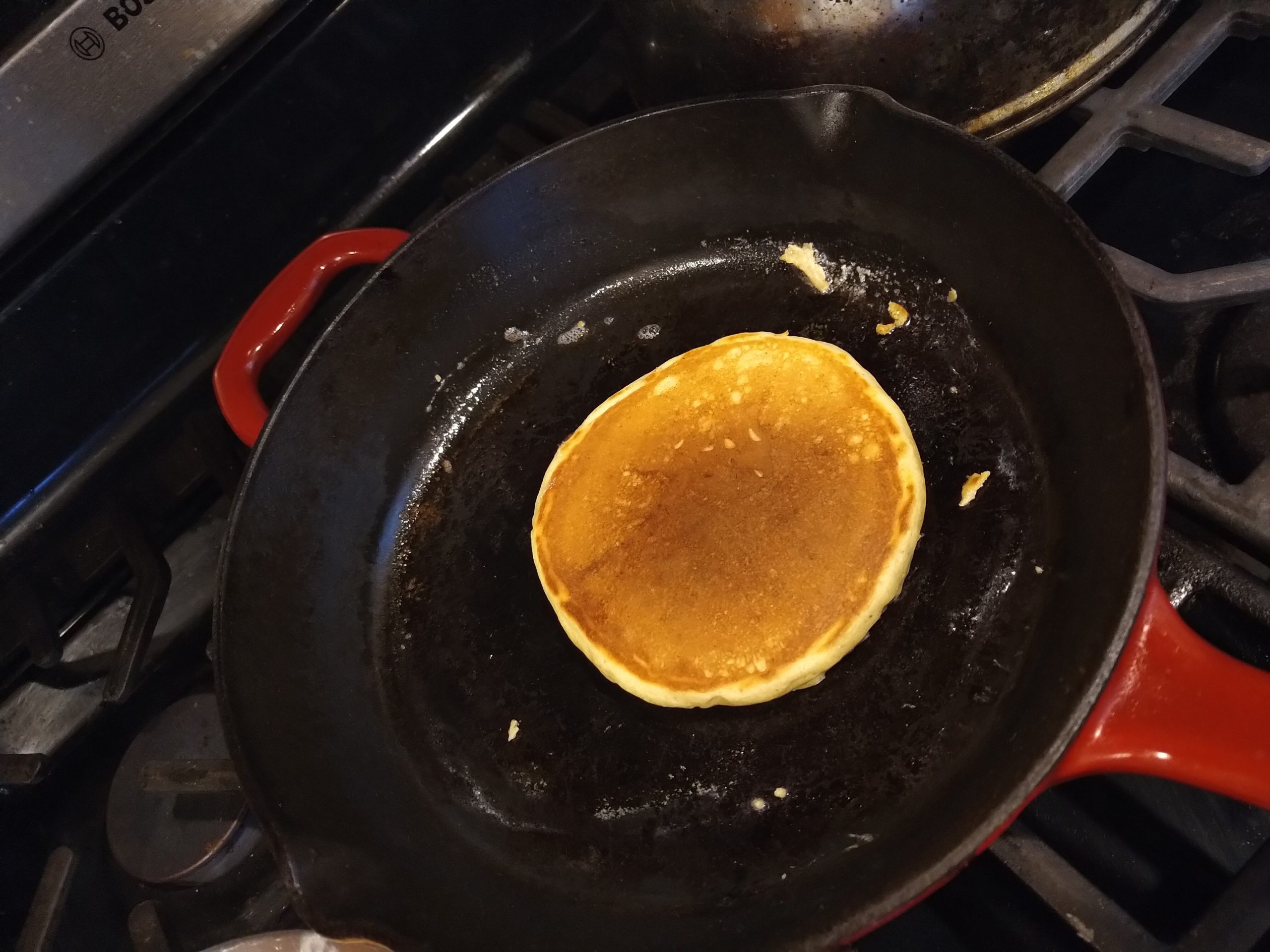

As I read my shero’s notes and gathered the ingredients, I felt a deep connection to her. She was with me as I measured and mixed, as I heated the skillet just so.

Rosa Parks’ life was so unjust and difficult. As a young girl, when the Klan terrorized her town, she had to stay awake all night, the windows of her grandparents’ home boarded up and her grandfather sitting in the rocker with a gun across his lap, prepared to do whatever was necessary to protect his family. As a young woman, she spent her non-working hours investigating sexual assaults against Black women for the NAACP.

During the boycott, she endured near-constant death threats and lost her livelihood. (She and her husband dealt with financial insecurity for many years after the boycott ended, even after they moved to Detroit.) She suffered stress-related health problems, including painful, persistent ulcers. Despite being introverted and extremely private, she spoke at large events across the country and submitted to countless interviews.

And yet, on some mornings, in the midst of the trauma and uncertainty and physical suffering, she rose early and mixed batter, stood patiently at the stove until it began to bubble, served stacks of fluffy featherlites to loved ones—with butter and syrup, or powdered sugar and jam—perhaps with a side of bacon or grits or scrambled eggs.

I was comforted by this thought then, and I am again now, as I set my alarm to wake early tomorrow morning and cook Sister Rosa’s famous featherlites for my family.

Image description: a tall stack of pancakes on a plate

“Memories of our lives, of our works and our deeds, will continue in others.” – Rosa Parks