My second child, known as “Baby” Busling on this blog, is nonbinary.*

They’ve been telling us in different ways throughout their 10 years on this planet, but they told me directly—or as directly as they had language for—at age seven. The words they used were “gender neutral,” and they explained those words to mean that they didn’t feel like a boy or a girl, or maybe they felt like both a boy and a girl, or maybe, they felt like something beyond all of it, something that English does not have a word for.

When they first told me, I said all the correct, affirming things that parents are supposed to say in these situations.

But inside, I was devastated. I didn’t want a ticket for this particular ride. Even as I searched for children’s books about gender and met with teachers to discuss my child’s identity, I secretly hoped this was a “phase” they would soon outgrow.

For one thing, I simply didn’t understand.** We had raised our children to question gender expectations and norms. We had told them that their gender did not limit who they could be in this world. I wondered: If my child can be a boy and still dress and act and be however they please, why do they need a different label for it? And if they grew up understanding that boys come in all different packages, how do they know—in their bones—that they aren’t a boy?

But much stronger than the confusion, which I could live with, was the fear. I was devastated, not because I believed that there was something wrong with my child, but because I knew there was a lot wrong with the world they lived in.

Raising a Black child in this sick, violent, white supremacist culture is terrifying. I have struggled with that truth since my daughter was born in 2007. But at least a Black child can find some refuge, encouragement, and safety in the Black community. Where can a Black transgender child find refuge, encouragement, and safety?

Every time I looked to my sweet Busling’s future, all I saw was rejection and violence. In those first months (really, years), I was ruled by fear. And if I’m honest, it wasn’t just for my kid; I knew that the rejection would extend to me. My parenting would be questioned. I would be forced to reckon with bigotry in what had previously felt like circles of safety.

In other words, I could no longer simply profess solidarity with transgender people. I could no longer limit my support to sharing my pronouns or participating in the occasional march. I would have to live in the world from the other side of the divide, to actually experience the contempt, the erasure, and yes, the danger.

But fear is one thing. And love—love—is another.

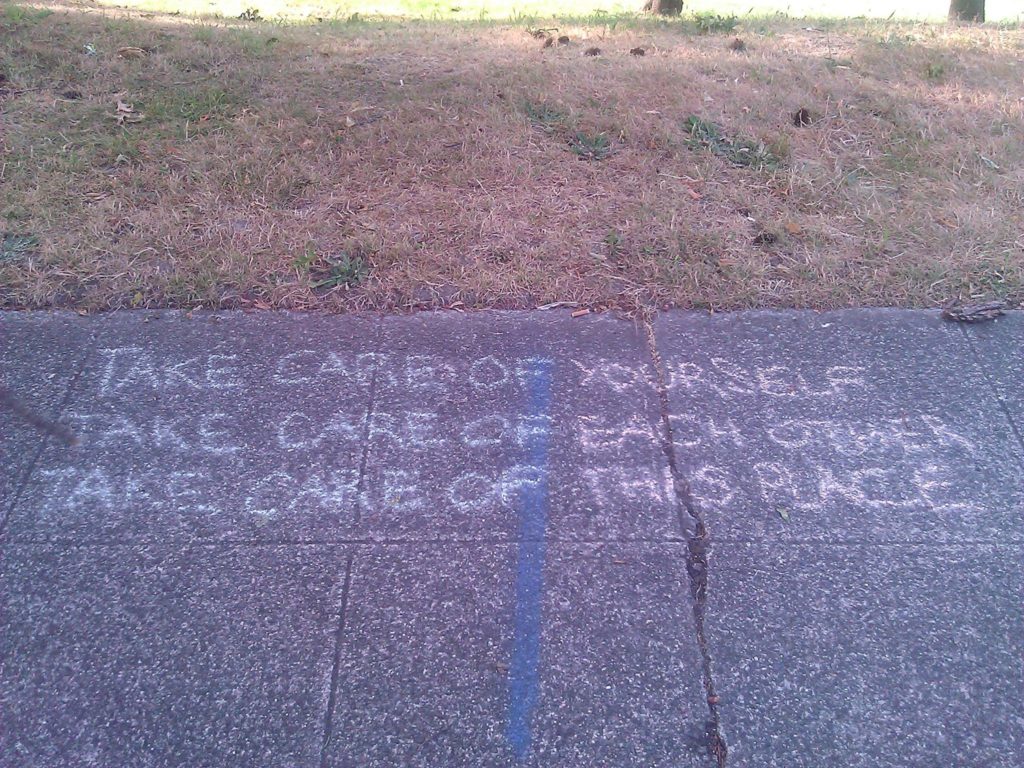

I can’t make the world safe for my child. Full stop. But I can make my heart and my home safe for them. I can walk beside them with pride. I can stare down bigotry whenever (and in whomever) it arises and insist that everyone in my child’s life honor their full humanity.

I don’t understand what gender is. But the one thing I know for sure is that my child is beautiful.

They have always seen the world from a particular vantage point. For as long as they’ve been able to talk, they’ve astounded me with their astute, insightful observations. I’m constantly asking myself how it is that it took me over 40 years to unlearn nonsense that this oracle of a human sees through right away.

Busling is a gifted visual artist, writer, and dancer. They enjoy origami, welding, basketball, baking, and nurturing almost anything living. They hate bathing and practically live in torn, stained t-shirts and jeans, but they also love dressing up in fancy, sparkly outfits and gathering dropped camellia flowers to pin in their hair.

They will play any game (outside or in), with anyone, anytime. If I walk by someone on the street in need of help and neglect to stop, they always remind me. “Mom, didn’t you see? That person needs a few dollars for food.”

If this is what it means for my perfectly made, second-born child to be who they are, why would I want them to change? Why would I want them to “fit in”? I can’t take the particular beauty of this particular human and leave their gender. It’s one package.

Watching the person I had the honor to bring into this world understand, name, and embrace who they are has shown me who I am. And I don’t like what I see in that mirror.

I am a rule follower, someone who regularly chooses acceptance and approval over truth and freedom. I have spent my life tiptoeing and contorting, hoping to be liked, to be picked, to be “good.” As a child, I was such a pleaser that I rarely even knew what I wanted; I just automatically did what was expected of me. Because I didn’t know how to be true to myself, pain and confusion leaked out in other ways. It’s been a long road back to me, and to be honest, I’m still on it.

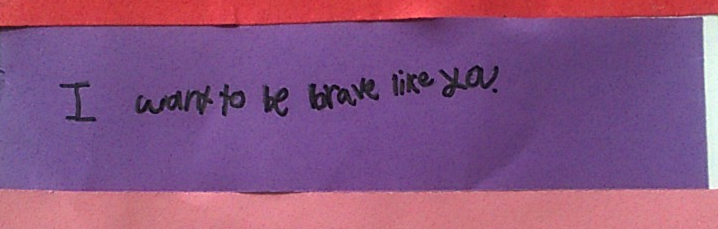

Thank god for beautiful Busling, my teacher. I watch the way they look inside for guidance, the way they walk in the world with courage, and I am convicted.

I am honored to walk beside them on this journey.

***

*If you don’t know what this means, the Gender Reveal podcast has a really great Gender 101 episode.

**I’ll admit that I still don’t—at least not fully. But my child’s identity is not for me to understand. It’s for me to support and accept.