Last Friday, on a Portland light rail train, a white supremacist verbally abused and threatened two nonwhite teenage girls (one of whom was wearing a hijab) and then stabbed three men who tried to intervene, killing two of them.

Since I first learned about this horrific incident, I haven’t been able to think of much else.

For me, public transportation is a space to feel and be a part of my community. And a crowded train in broad daylight is one of the safest places I can imagine. I am not naïve. I know that sharing space with others isn’t always easy or pleasant and that transit reflects all of who we are, including our ugliness. What happened in Portland last week was a reminder that the ugliness can surface at any time, even in broad daylight on a crowded train.

When I was in my teens and early twenties, I endured near constant harassment by grown men — on transit trips and otherwise. And, like every person of color in this country, I have experienced my share of name-calling and other forms of direct, in-your-face racism. I know that feeling of vulnerability, the stress of staying vigilant and alert for the entirety of every outing, so I can easily imagine the fear, rage, and humiliation those young women felt when an unhinged stranger loomed over them spewing hate.

I can also imagine what it felt like to be on the train when the incident happened. I understand the desire to turn away from conflict or confrontation, especially if you are personally vulnerable. Rachel Macy, a passenger on that devastating ride, described her initial fear in an interview with The Oregonian.

“I didn’t want to look. I was too afraid. It felt really tense,” said the 45-year-old Southeast Portland resident of Native American descent. “I’m a woman of color. I didn’t want him to notice me.”

She found her courage a short time later, when she rushed to the aid of one of the victims and comforted him in his last moments of life.

Of course, the perceived threat was not the same for the men who did step in. Most likely, they did not imagine that the encounter would end their lives. But certainly, it would have been easier to look away, to turn up their headphones, to wait for someone else to help.

Those men did not turn away. And their decision to act with compassion and decency did end their lives.

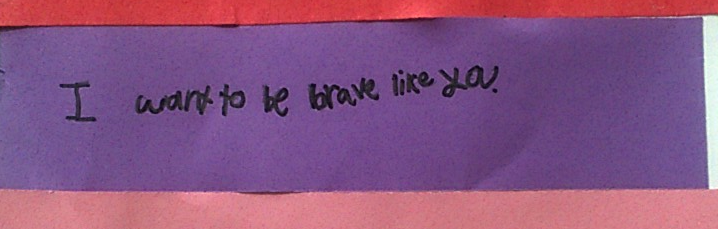

What happened to these brave people should not be a cautionary tale; it should be a call to action. We cannot turn away from the evil that is happening around us — in our schools or workplaces or in the adjacent aisle on the train. We must stand and face it. We must defend the dignity of our fellow humans. Standing up might risk our lives, but it will save our souls.

Thank you, Ricky John Best, Taliesin Myrddin Namkai Meche, and Micah David-Cole Fletcher.

“The question is not, ‘if stop to help this man in need, what will happen to me?’ The question is, ‘if I do not stop to help [the man] what will happen to him?’” – Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. on the Parable of the Good Samaritan